From football to acting, boxing to writing, and now, directing, Matt Nable has long defied stereotypes. And now he’s ready to smash some more, speaking candidly about his mental health issues and more.

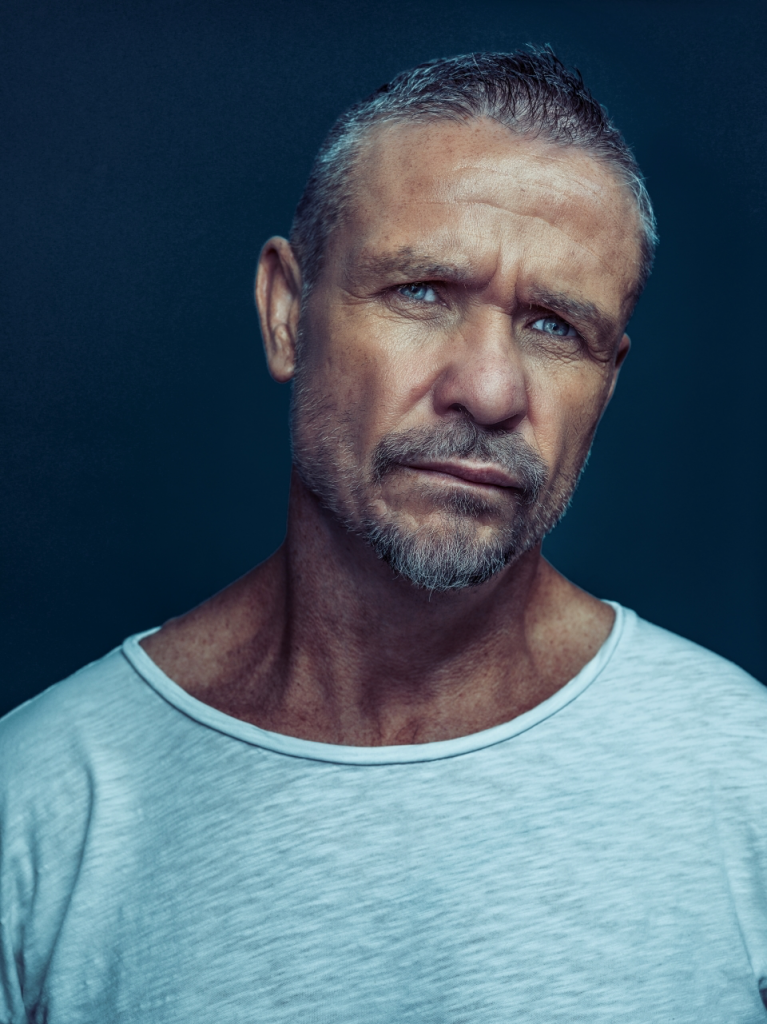

On a bright autumn morning at the Glenrose Village Shopping Centre in Sydney’s northern suburbs, near tables occupied by a young mother with a burbling toddler, a middle-aged woman reading a propped-up iPad and a retired gent nursing a cappuccino, Matt Nable stands out. For one thing, it’s his appearance. At 51, Nable is an actor, screenwriter, novelist and now film director – largely self-taught in every one of these fields. But he’s also a ruggedly fit former rugby league player for Manly-Warringah Sea Eagles and South Sydney Rabbitohs, who later fought for a state light-heavyweight amateur boxing title.

Wearing khaki cargo pants and a tight green T-shirt, with close-cropped greying hair, a light beard and tattoos on both arms, he looks like a battle-hardened soldier who’s dropped in for a triple-shot espresso between boot camp and the weights room. Well, hobbled in, really. The previous week, Nable had a knee replacement that dates back to a football injury at the age of 19, so he’s charging around with a cane.

But neither the look nor the cane are why Nable stands out. It’s that, as oblivious shoppers push their trolleys towards the car park and teenagers ride by on their bikes, he’s quietly crying. It’s something he’s been doing a lot of, lately.

Nable starts talking about how close he is with his three brothers and sister, then chokes up. The Nable kids grew up in military barracks around the country. Their dad, Dave, was in the army; mum, Kristine, had five kids – Matt is the second-oldest – by the time she was 27. The family moved from Holsworthy in south-western Sydney to Albury-Wodonga, then Portsea in Victoria, Duntroon in Canberra, then back to Sydney to the School of Artillery at North Head. “It’s hard not to be emotional,” Nable says through tears. “It made us really close, because we just had each other.”

With that bond, he’s been particularly affected by the diagnosis of younger brother Aaron with motor neurone disease (MND), a devastating neurodegenerative condition. The 45-year-old, who has sons aged 10, two and one, is a former national amateur boxing champion who trained under the legendary Johnny Lewis and sparred regularly with four-time professional world champion Kostya Tszyu. There’s no cure for MND and the average life expectancy for what he has, Bulbar onset MND, is six months to three years. Aaron was diagnosed in July last year. “This disease, what it does is just the hardest thing to watch,” Nable says.

The next night, he emails to say he’s in a vulnerable state because of what his brother is going through. “I’ve cried lots today,” he writes. “He’s frightened and I can’t do anything to help him. I make him laugh, we remember things from our past. He knows I’m right beside him.” As disruptive as it was being what he calls “displaced kids”, Nable is thankful now for how he and his siblings were brought up. “There were times when it was just us, five kids in one bedroom,” he says. “Aaron slept with me until he was nine or 10. He and I were scared of everything; certain we were always dying of something. And he was so scared of something happening to our mum.”

Way back on a wintry afternoon in 2007, Matt Nable was just another face in a scattered crowd watching the Newtown rugby league team play at Henson Park in Sydney’s inner west. As a chilly wind whipped across the hill, kids and scrappy dogs were chasing footballs, fans were sipping old-school KB and the club’s ancient anthem was blasting through the PA: Newtown is coming/hear the Bluebags humming/Newtown/Newtown.

Nable’s first film as a scriptwriter and actor, the drama The Final Winter, had screened to a warm reception at the Sydney Film Festival six weeks earlier and was about to open in cinemas. In it, he stars as fictional Newtown rugby league champion Mick “Grub” Henderson, who is in the final week of his playing career. So a Newtown match was the ideal place for an interview and photo for The Sydney Morning Herald.

‘It felt quite raw. My wife can testify to that, because for the five weeks I went through that journey as an actor, I wasn’t the nicest person to be around.’ – MATT NABLE

At the time, Nable came across as a rugged and thoughtful character, who described acting in the film as the hardest thing he’d ever done. “Because Grub goes on such an emotional ride, to get myself to such emotional spots was immensely difficult,” he told me then. “It felt quite raw. My wife can testify to that, because for the five weeks I went through that journey as an actor, I wasn’t the nicest person to be around.”

Sixteen years on, Nable is a rarity: an actor, screenwriter, novelist and director who has a background in brutal professional sport but is open about his vulnerabilities and mental health struggles.

Although it wasn’t diagnosed until 2012, he’s been dealing with bipolar disorder since his teens, cycling through extreme highs and lows, and suffering from melancholy depression. He believes talking about it could help others. “We lose too many people to suicide every day,” he says. “The alarming statistic is men.”

Back in 2007, I was impressed with what he’d done with that first film. While working in sales for a brewery, Nable had mapped out the story in his car between appointments. And despite having only acted once before – as a fox in a school play – he brought a raw, emotional intensity to Grub.

Nable was always a sporty kid; one of his first memories is of being put into the ring, at the age of three or four, to box other boys at an army-navy-air force fight night. After his father left the army, the family moved to a house overlooking Brookvale Oval, where Manly trained and played. Nable senior became the strength and conditioning trainer under coach Bob Fulton, then took on the same role with the Kangaroos when Fulton coached the national rugby league team.

At the local Christian Brothers college, Matt Nable was a diligent student. “I was afraid of getting in trouble,” he says. “I wanted to do well and I was always able to write.” He was a good enough rugby league player in Manly’s junior teams to make the NSW under-17 and under-19 teams.

There were some great players there, including future stars Brad Fittler, Terry Hill and Brett Mullins – but Nable freely admits, “I just wasn’t one of them.” But he was good enough to play on. Older brother Damien also played in the lower grades for Manly, while younger brother Adam had a successful career that included seasons with Manly, the Balmain Tigers and the North Queensland Cowboys.

When Nable didn’t get the marks to study journalism at university, he began a knockabout time that included pumping concrete, working in a hotel bottle shop, then driving around the country with a mate in an old Torana during the off-season. He studied to become an English teacher at the Australian Catholic University (for all of four months), then later became “the world’s worst carpenter”.

Starting as a lock, Nable played five first-grade matches for Manly then, at 21, moved to Souths for more opportunities. He had another three first-grade games there before realising he wasn’t enjoying it any more. “I didn’t have the disposition to turn up every week mentally to do what I needed to do,” he says. “My head was in the clouds. I was daydreaming.”

Nable went travelling overseas and ended up playing in England for Carlisle, then for the London Broncos, before retiring from rugby league at 25. Without telling anyone, he started writing a novel that became The Final Winter. It was set in a world he knew well: the knock-down, drag-out era of rugby league that he’d loved growing up in in the 1980s.

Back in Sydney, Nable took up amateur boxing and married Cassandra, the younger sister of one of his high school and football mates, who worked in sales for a personal-care products manufacturer. And he kept writing.

By the time he was 30, Nable and Cass had bought a house at Forestville in the northern suburbs, he had a well-paid job with a brewery and they were planning a family. But he was plagued by a feeling he was underachieving. “I thought, ‘Okay, in the next year, I’m going to do three things,’ ” he says. ” ‘I’m going to fight for the state championship. Whether I win or lose, I’m going to get tested and I’ll give it everything I can. I’m going to learn an instrument. And I’m going to finish this manuscript I’ve started.’ And in 12 months, I’d done it all.”

Nable lost his state title fight – his trainer, Johnny Lewis, jokes that “as a footballer, he made a good boxer but as a boxer, he made a good footballer.”

He learnt the guitar. And he finished the manuscript that, via an old teammate who was working for the Sea Eagles, he showed to Booker Prize-winning novelist Thomas Keneally, one of Manly’s most passionate fans.

Keneally knew Nable’s family as “famous tough guys” around the club. “Of course Matt isn’t a tough guy,” he adds. “He’s a very gentle soul.” Johnny Lewis agrees, though he once questioned Nable’s sanity when he saw him fighting four opposition players in a rugby league match.

The Schindler’s Ark author was encouraging, but it wasn’t until Nable had written his second manuscript, which became the novel We Don’t Live Here Anymore, that Keneally was convinced he was a real writer. Nable remembers Keneally ringing out of the blue in 2005 to say, “Son, this is what you should be doing.” Still impish at 87, Keneally remembers the call well: “I broke the news to him that he was a very good writer. It’s like breaking the news that you’ll be an alcoholic for the rest of your life. It shouldn’t be done lightly.”

Nable quit the brewery that week and became a full-time writer. He turned that first manuscript, which had started as a novel, into the script for The Final Winter. Nable and two longtime friends formed a production company and raised $1.6 million to make the film from a group of businessmen, including adman and former Newtown Jets owner John Singleton. Nable asked directors Brian Andrews and Jane Forrest for the chance to play Grub. “The perfect guy in our mind was Russell Crowe but we just didn’t have the money or the resources to get to him,” Nable says. “So I just put my hand up and said, ‘I’d like to have a go. If I suck, get rid of me and just make the film.’ I knew if I hadn’t tried, I’d be kicking myself.”

‘I broke the news to him that he was a very good writer. It’s like breaking the news that you’ll be an alcoholic for the rest of your life. It shouldn’t be done lightly.’ – THOMAS KENEALLY

Nable nailed the performance – capturing the essence of a blue-collar player from the ’80s – in a film with deeper underlying themes about Australian men with a tough exterior struggling with their identities in a fast-changing world. Keneally enjoyed a cameo as a gatekeeper; brother Aaron played a Jets player; father Dave was the team’s trainer; and former league star Matty Johns was their coach.

Then: disaster. The Final Winter opened in cinemas on what turned out to be the worst weekend possible, the start of the NRL semi-finals, when fans had a full schedule of matches to watch. The film flopped. “Look, it was disappointing at the time,” Nable says. “But we were really proud of that movie and it holds up.”

By chance, an American casting agent was scouting in Sydney for the lead for an American crime telemovie SIS: Special Investigation Section. Nable taped an audition, won the role and shortly after, arrived on set in Phoenix, Arizona, to shoot the pilot. Cass and their two then infants joined him for part of the shoot.

“I had people telling me, ‘You’re going to be a movie star, you’re going to be this and that,’ ” Nable says. “It was just too overwhelming to filter.” Then: nothing. The series wasn’t commissioned and Nable was back in Sydney without any acting jobs.

“Between 2008 and 2010, I barely worked,” Nable says today. “I must have had 300 auditions and got three jobs. I realised I’m just in this big pool with everyone else and I’m not anything special. I’m just someone else fighting for a job.” It wasn’t until 2011, when he landed a role as a detective in the SBS series East West 101, that he finally got some traction as an actor. The following year, he gave gritty performances on opposite sides of the law: as Comanchero leader Jock Ross in Bikie Wars: Brothers In Arms, then as detective Gary Jubelin in Underbelly: Badness.

There were big American roles, too, starting with playing a former SAS operative in the 2011 crime thriller Killer Elite, which starred Jason Statham, Robert De Niro and Clive Owen, then playing a bounty hunter opposite Vin Diesel in the 2013 sci-fi sequel Riddick. His American agent was so optimistic he’d land another movie on the back of Riddick that Nable turned down a regular role on Game Of Thrones.

“That was a sliding-doors moment,” he says. “But I’m not into dragons and period pieces that much, so it wasn’t something that really interested me from an acting point of view. I’m disappointed financially but I could have gone to Ireland [for the shoot] and, with my issues, the wheels could have well and truly fallen off there without my family.” Nable later played a villain in the 2014-15 superhero series Arrow, shot in Vancouver.

His novel We Don’t Live Here Anymore, meanwhile, about an encounter on a beach between an awkward teenage boy and a girl that affects the course of his life, had been published in 2009 to encouraging reviews. Nable wrote another novel, Faces In The Clouds, about twins whose parents are killed in a car crash, which came out two years later.

He continued to write in his car. Even now, he drives his Ford Wildtrak to somewhere he won’t be interrupted, pulls back the driver’s seat and types on his laptop. “It’s where I feel comfortable writing,” he says. “And I can go wherever I like. I can drive somewhere, have a break, then drive somewhere else.”

Nable is today a familiar face on Australian screens, having played a suite of what he calls “authoritative figures – either really good guys or really bad guys”. They are often cops (in the TV series Winter, Hyde & Seek, Blue Murder: Killer Cop and Dead Lucky and in the film Jasper Jones) or crims (in the series Mr Inbetween and Last King of the Cross and in films Around The Block, Son Of A Gun and Poker Face). Sometimes he plays military officers (in the series Gallipoli and the film Hacksaw Ridge).

He’s also played an abusive husband (The Turning), a mental patient who thought he was Harold Holt (Wakefield) and a tormented father (The Twelve). In the past decade, Nable has written two more films – both intense dramas – and played a lead role in both. He was a hulking bikie boss in 2017’s 1% (also known as Outlaws) and a damaged former SAS soldier who had turned to crime in this year’s Transfusion, which was also his debut as a director.

While his career took a while to warm up, Nable has finally found his rhythm. “I can’t do everything,” he says of his acting. “I’m a rugged-looking person and I’m a physical guy, and that will never leave me – and there’s a demand for that. You can push back on it, if you want to, or you can embrace it, like I have.

“Directing wasn’t something that I had great ambition to do. It seemed like an evolution from writing. If you want to control the tone and have your fingerprints more solidly on something – and I did – that seemed to be the next step.”

Robert Connolly, who directed him as a Hungarian-born swim coach in the 2016 ABC series Barracuda and the simmering cousin of a dead teenage girl in 2020’s The Dry, sees Nable as “quite an extraordinary figure” in the Australian industry. “He brings a really interesting perspective to his work, as a writer and now as a director,” he says. “But as an actor, it’s just these big humanist performances that he gives – deeply truthful and heartbreaking.”

While he’s been nominated for four AACTA awards (for acting in Barracuda, Blue Murder: Killer Cop and Mr Inbetween and for writing 1%) and two Silver Logies, Nable’s best performance is in the little-seen 2014 film, Fell. In it, he plays a grieving father who changes identity to seek revenge on a timber-truck driver who killed his young daughter in a hit-and-run accident. “When I did Fell, I was the father of three very young kids and, to this day, it doesn’t go away, the fear of their mortality,” Nable says. (His son Tommy is now 18, Jesse 16, and Leia, 13.) “You get an opportunity to explore the compassionate, gentle, vulnerable side that I have. I’m an immensely emotional person.”

‘When I did Fell, I was the father of three very young kids and, to this day, it doesn’t go away, the fear of their mortality.’ – MATT NABLE

Transfusion features Sam Worthington as a former SAS soldier who is grieving for his late wife, played by Phoebe Tonkin, and drawn into a robbery when he needs money fast. While streaming services don’t disclose viewing numbers, Stan [owned by Nine, the publisher of Good Weekend], where it’s now showing, describes it as a successful summer release.

As well as being impressed with Nable’s directing, Tonkin is a long-time admirer of his acting. “Matt is an incredibly layered, emotionally deep individual,” she says from Los Angeles. “What makes him such a beautiful actor is there’s a real depth and emotional gravity that he brings to all these roles, no matter how tough on the outside they are.”

Between all this acting work, Nable had two more novels published: Guilt in 2015, about how the events of a night in 1989 haunt a group of students in their adult lives, and Still in 2021, a crime thriller about a detective investigating a murder in Darwin in 1963.

He has a busy year ahead, with plans to direct a second film, based on another script he’s written about “the epidemic of loneliness”, in New York later this year. He is planning a fifth novel, Mire, and is pencilled in to write a six-part adaptation of Still for a streaming service, with Vikings’ Travis Fimmel slated to star.

As well as these projects, Nable wants to raise funds for MND research and for his brother’s family. A fundraising event held in Pyrmont last December, called Lunch with Legends, showed how interconnected he now is to colourful, disparate worlds across Sydney. Hosted by broadcaster Ben Fordham, the 650-strong audience included Fordham’s talent-manager brother Nick (who manages Nable), former NRL stars, detectives, ex-nightclub owner John Ibrahim, actors Richard Roxburgh, Silvia Colloca and Susie Porter, ex-boxers, MND researchers and 150 wharfies who worked with Aaron on the Port Botany wharves until he got sick. The lunch and a GoFundMe campaign have raised more than $300,000 so far.

“One in 200 people gets MND,” Nable says. “In 1985, it was one in 500, so there’s something environmental that’s causing that spike. And it’s important they find a cure, because what it does to a human being is catastrophic. It’s the definition of sadness.”

Two days after those tears at the cafe, Nable takes me to see Aaron, who is living with their parents in the same place they grew up in at Brookvale. We wait in a living room that’s been reconfigured to include a double bed so family members can stay over. Aaron’s carer, Vicki, helps him out of bed.

Once described as Australian boxing’s brightest 2000 Olympics medal prospect, Aaron is tall and lean, with tattoos of Che Guevara and a Karl Marx quote (“Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains”) on his torso. He can no longer speak or swallow properly and is fed through a long, white tube into his stomach.

Matt gives his brother a hug and tells him he loves him. Aaron taps out a message on his phone for his mum, Kristine. “He says he doesn’t want to die yet,” she says, tearing up. After breakfast, Aaron wants to watch the crime drama In the Name of the Father. Given his Che tattoo, I ask if he’s seen The Motorcycle Diaries. He nods enthusiastically, sharp and engaged as his body fails him.

The family has rallied around. As soon as he was diagnosed, the four brothers and their mates booked a trip to Vegas. They took in a world title fight, an NFL match and partied by the pool in what Nable calls “a once-in-a-lifetime trip”. Aaron needs a wheelchair now, but the brothers take him out whenever they can: to Johnny Lewis’s 79th birthday in Balmain, to watch Manly play the Knights in Mudgee, to a farm in the Hunter Valley. It’s a short visit, just 20 minutes. “Aaron would be embarrassed, watching him being fed like that,” a sombre Nable says as we leave.

Mental health was once something very few people were comfortable talking about, especially those with a background in rugby league and boxing. Around the time Nable was being recognised as an acting talent in Bikie Wars and Blue Murder, there was a day he refers to as “rock bottom”, a near-tragedy recognised by a tattoo on his left wrist: “December 2012″. Depression made the world go impossibly dark that day.

Nable says he was “up somewhere very high” in Manly. “I’d made plans and they were materialising very quickly,” he says. “You can have a series of bad days, then have an extra-bad day and start making plans. That’s how quickly it can happen.” He’s still not sure why he was able to get himself out of there. “It wasn’t anything profound, I didn’t have a revelation,” he says. “I just walked away from where I was and got myself home. I consider myself lucky.”

Wife Cass, 48, now works in marketing for the suicide-prevention foundation, Gotcha4Life. She says they were “very lucky” and that Nable went on antidepressant medication after the incident. “Matt said at the time that the thing that probably prevented him from taking that step was the pain he would leave behind,” she says. “Although he wanted to end his own pain, he couldn’t inflict that pain on everyone else.”

Nable has other tattoos that reflect his mental health struggles: happy and sad “drama faces” embellished with birds flying, which represent bipolar states; an anchor that symbolises that he needs to keep grounded; and quotes from Muhammad Ali (“the man who has no imagination has no wings”) and Ernest Hemingway (“the world breaks everyone then some are strong in the broken places”).

He says he was relieved to be diagnosed with bipolar II – less severe than bipolar I – after the “rock bottom” drama of 2012. It explained the extreme highs and lows that became “problematic” when he had a young family. The disorder is said to affect people in the performing arts at five times the rate of the general population, including the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Kanye West, Stephen Fry, Robbie Williams, Russell Brand and the late Carrie Fisher and Margot Kidder. Rugby league stars Andrew Johns, Greg Inglis and, just this year, Angus Crichton, have also been diagnosed with it.

“My disorder doesn’t just manifest itself in being the hypomanic, happy ‘life of the party’ and then exacerbating that with alcohol or drugs,” Nable says. “The highs that you feel, the sense of euphoria, that’s just one side of it. The other side of hypomania is being agitated and irritable and not able to sleep.”

Cass says their children know what their father is dealing with and make sure they talk about it. “We’ve always talked about mental health in the family,” she says. “No matter what’s going on, we make sure that it’s not a taboo subject.”

Nable says therapy has helped him avoid losing his way. “Over the last 10 or 12 years I’ve seen a psychologist, and at different times it’s been remarkably beneficial.” But he can still feel himself “bubbling” occasionally. His most recent bipolar episode was triggered by watching a favourite musician perform. “I was at Collaroy Services Beach Club crying, listening to this song that threw up all these memories,” he says. “I was like, ‘I’m f—ed. But I’m here now, I’m not leaving. I’m going to continue drinking and this feels so amazing and so good.’ I got home at 10 o’clock or whatever. I was drunk, super-high. I probably ironed clothes for – I don’t know – three hours. Like a maniac, just ironing and ironing and ironing.”

‘The depression never leaves. I wake up flat most days. The first thing I do in the morning is be with my kids.’ – MATT NABLE

There was another episode at the shops, also triggered by listening to music, that led him to drinking at 10am. Nable has talked with rugby league great Andrew Johns about how seasonal changes like the start of spring can also set off an episode. While it can lead to destructive behaviour, a corresponding surge in confidence can also inspire creativity. “You can get a lot of work done when you’re in a manic episode,” Nable says. “I’m not an actor if I’m not bipolar. If I’m not bipolar, I’m certainly not deciding that I’m going to make a movie and put myself in it. The confidence that I display to do that isn’t real.”

Nable accepts that he will be managing the disorder for the rest of his life. But depression is more challenging. “The depression never leaves,” he says. “I wake up flat most days. The first thing I do in the morning is be with my kids. I’ve got to drive them somewhere, we talk, interact, we try to laugh. That’s a big part of my morning, to get me firing again.

“The hardest thing with depression is that there doesn’t seem any rhyme or reason as to why you fall into darkness but, for me, when it gets dark, it gets really dark. I’m lucky that I’ve had people to drag me back into the light. Bipolar doesn’t scare me. Depression does.”

Observes Thomas Keneally: “It’s a comfort to know that a man you thought was made of steel is languishing with all sorts of doubts and is subject to fits of profound depression. Matt is hugely intelligent and I think it’s great that he’s willing to talk about it. It’s part of his can-do attitude: ‘Let’s make a movie and, on the way, let’s make sure we deal with the demon within as well.’ ” Keneally, who says he’s “a bit of a wacko myself”, adds that struggle is just part of the human condition. “We are born incomplete. The theologians call it original sin. I call it just being lost in the world and finding your bearings.” Nable, thankfully, seems to have found his.